git bisect and the importance of a clean history

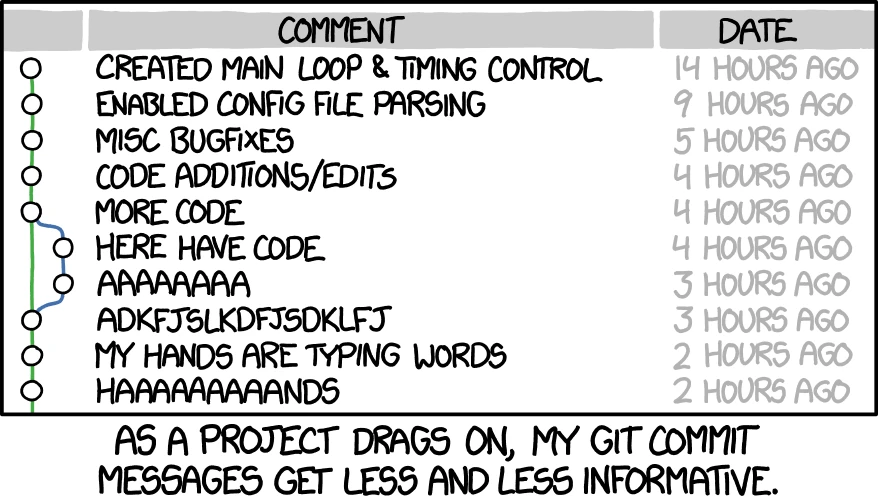

Most of the projects respectively teams I have seen so far do not seem to care too much about a clean git history. Therefore the git history of many projects look more like the following comic shows:

Of course, xkcd might try to exaggerate a bit, but unfortunately, I have seen commit messages like those way too often. This includes messages like:

- adding stuff (what stuff? this could be about anything)

- fix bug (that does not even scratch the surface)

- iuwqruphsdauifj (aka just hitting the keyboard)

- fix CI (this one is often repeated in multiple consecutive commits and followed by one using swear words)

A good commit message acts as documentation and can be immensely helpful when trying to figure something out later.

Very often only single-line commit messages are used (I am guilty of that myself), but even the git commit

documentation page mentions that it is recommended to begin a commit

using a short line acting as a heading, which can be followed by a thorough description. An example of a thorough

description is this (at the time of writing) recent commit in the Linux

kernel.

Yes, almost everything until the start of the diff itself is the commit message, and while I am not that fluent with the

development of an operating system, I am pretty sure that there is quite some interesting information in it, which

might be useful when hunting down a bug or trying to better understand some decisions later.

But having a clean commit history does not stop at commit messages. Although this is already a big help, git can help a lot more when it is being mastered. Some features only work well if branches are kept healthy, i.e. every commit represents a working state. So instead of just ending with saying that a clean history is important, I would like to promote an in my opinion way too unpopular feature of git.

Finding bugs with git bisect

Some time ago I prepared a small example in my git-bisect-example

repository, which contains a small application written in

Node.js. This application is a very simple calculator, which has been implemented incrementally

using multiple commits. Unfortunately, one of these commits contains an error, which leads the + operator to subtract

two numbers.

$ node index.js

First operator: 5

Operator: +

Second operator: 2

3

So everybody who knows basic arithmetic should see that there is something odd here. What seems even odder to the

development team is that they are absolutely certain that this was working properly at some point. So after looking at

the output of git log they remember that the addition of two numbers was working properly after the commit

d3c66b49c330e58a70fe0abda56b691e1bb5db75. So they switch to this commit

and execute the program again.

$ git switch -d d3c66b49c330e58a70fe0abda56b691e1bb5db75

HEAD is now at d3c66b4 Refactor to use switch to differ between different operators

$ node index.js

First operator: 5

Operator: +

Second operator: 2

7

This shows that the development team was right about that, and the problem space has been reduced to a specific set of commits. Now a developer can go through all of those commits, test again, and can find the (hopefully small) commit causing the issue. However, if the issues persisted for quite a long time there could be hundreds of commits in between, which still results in a very high effort.

Luckily, git comes with an awesome command called git bisect. bisect stands for “binary search commit”, and this is

exactly what it does (Edit: I’ve been told that bisect is actually a word on its

own, meaning to cut in half, not sure where I got this “binary search commit” theory

from). It performs a binary search using the git history,

which leads to much less effort when looking for a specific commit. Let’s see how that works in practice.

First of all the binary search is started using git bisect start followed by a git bisect good indicating that the

currently checked out commit is not working.

$ git bisect start

status: waiting for both good and bad commits

$ git bisect good

status: waiting for bad commit, 1 good commit known

Afterwards, git switch - is used to checkout the previously checked out commit, which was failing before. Therefore we

can mark this commit as working using git bisect bad.

$ git switch -

warning: you are switching branch while bisecting

Previous HEAD position was d3c66b4 Refactor to use switch to differ between different operators

Switched to branch 'master'

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

$ git bisect bad

Bisecting: 2 revisions left to test after this (roughly 1 step)

[3eaa08756c7ae6273effa173a3aba7d1fe4a8929] Added support for multiplication

By marking one commit as bad and one as good we have defined the range in which the error must have been introduced. After doing so, git has checked out the commit in the middle of the range. Now we can do the same test again, realize that the error does not happen in this commit, and mark it as a good one.

$ node index.js

First operator: 5

Operator: +

Second operator: 2

7

$ git bisect good

Bisecting: 0 revisions left to test after this (roughly 1 step)

[124439abe0fb289109f915dcdd07f1ecb0041f79] Add support for subtraction

By doing so half of the commits have already been eliminated as the cause of the bug. Since the older commit used to work and the commit in the middle of the range is still working, the error must be introduced later. Git knows that now and automatically checked out the next commit, which is in the middle of the even narrower range left.

So let’s test again and type git bisect bad afterwards since we will see that the error occurs now.

$ node index.js

First operator: 5

Operator: +

Second operator: 2

3

$ git bisect bad

Bisecting: 0 revisions left to test after this (roughly 0 steps)

[c4dc15f032ca15dcc84cd877a0babf4b0dfc1e8d] Add support for division

Again, the commits in question can be put in half, and git checks out the next commit for us to check. This one is working again, so we will mark it as a good commit.

$ node index.js

First operator: 5

Operator: +

Second operator: 3

8

$ git bisect good

124439abe0fb289109f915dcdd07f1ecb0041f79 is the first bad commit

commit 124439abe0fb289109f915dcdd07f1ecb0041f79

Author: Daniel Rotter <daniel.rotter@gmail.com>

Date: Sat Feb 19 11:12:05 2022 +0100

Add support for subtraction

index.js | 2 ++

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

Now git can already tell us the exact commit that caused the error. We can have a closer look by using the git show

command.

$ git show 124439abe0fb289109f915dcdd07f1ecb0041f79

commit 124439abe0fb289109f915dcdd07f1ecb0041f79

Author: Daniel Rotter <daniel.rotter@gmail.com>

Date: Sat Feb 19 11:12:05 2022 +0100

Add support for subtraction

diff --git a/index.js b/index.js

index 7800bbe..6a83dd9 100644

--- a/index.js

+++ b/index.js

@@ -9,6 +9,8 @@ let result;

switch (operator) {

case "+":

result = operand1 + operand2;

+ case "-":

+ result = operand1 - operand2;

break;

case "*":

result = operand1 * operand2;

Knowing that these two added lines are causing the error makes bug hunting a lot easier. In this example, the reason

was a missing break statement.

Now this was a rather small example, but the interesting part is that binary search has a logarithmic complexity, i.e. the savings get much bigger with an increasing number of commits, e.g. if the specified range contains 100 commits roughly 7 steps will be necessary to find the commit in question.

This process can even be further automated if there is a script that can tell if the code contains the error. In that

case the git bisect run command can be used, which will spare

developers from typing git bisect bad and git bisect good after testing for the defect manually.

The importance of a clean history

But now the catch: All of this can only work with a clean git history containing only working commits. Imagine that

the development team is not so strict about branches being healthy. This might lead to situations in which already the

bootstrapping of the application and therefore every program execution fails. In that case, the git bisect command

is rendered useless since developers using it cannot tell if the error they are looking for appears in the current

commit or if the program already failed before the error could appear.

Edit: Apparently there is also the possibility to skip commits during the git bisect process by executing git

bisect skip. I did not know about that when initially writing this blog post. This

might work somehow, but this feature is definitely easier to handle and produces better results with clean commits.

So having a clean and healthy branch is not just an academic exercise, if features like git bisect should be used

having a clean history is non-optional. And it would really be a pity to not be able to use one of git’s most awesome

features. This is one of the reasons I consider keeping all commits

green a best practice.

Keeping a clean history

As mentioned previously, it is not that easy to convince an entire team to only create green, i.e. working, commits. Especially if there is a workflow using pull requests in place it might also take quite some effort to check if all commits within this pull request are working. The problem is that the code hosting platforms I know only check the latest commit when a branch is pushed, i.e. if a developer commits multiple times locally and pushes all those commits at once the only thing a reviewer can say for sure is that the state from the last commit does not fail any pipeline (if one is setup).

I have seen quite a lot of arguing about this, but what works pretty well in my experience is to squash commits when a pull request is merged. Squashing means that instead of keeping all commits in the history they will be combined into one new single commit.

Imagine a git history that generates the following output when using git log --graph --oneline (i.e. showing the graph

on the left and compress commits to a single line):

$ git log --graph --oneline

* 8836470 (HEAD -> feature) Commit 6

* cec57f4 Commit 5

* c555d59 Commit 4

* e715723 Commit 3

* 55bc924 Commit 2

* 719d88d Commit 1

* 9ce9b8c (main) Initialize repository

So there is currently a branch called feature checked out, which adds some more commits on top of the main branch.

When we execute a git merge with the --no-ff option it will generate a new merge commit, which has two parent

commits and all currently existing commits continue to do so.

$ git switch main

Switched to branch 'main'

$ git merge --no-ff

Merge made by the 'ort' strategy.

README.md | 2 ++

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

$ git log --graph --oneline

* 8869431 (HEAD -> main) Merge branch 'feature'

|\

| * 8836470 (feature) Commit 6

| * cec57f4 Commit 5

| * c555d59 Commit 4

| * e715723 Commit 3

| * 55bc924 Commit 2

| * 719d88d Commit 1

|/

* 9ce9b8c Initialize repository

Now the graph on the left shows two different paths that will be combined in the merge commit. Seeing the entire

history with all commits can also be valuable, but only if all commits are properly working. If those commits are not

working and/or contain commit messages like shown in the introduction of this blog post they will cause more harm than

good by bloating the git history for no good reason. This complicates everything, especially the git bisect command

shown previously.

Squashing commits can be done by using the --squash option of the git merge command. Then the changes from all

commits will be added to the staging area, from where they can be committed as usual.

$ git merge --squash feature

Updating 9ce9b8c..8836470

Fast-forward

Squash commit -- not updating HEAD

README.md | 2 ++

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

$ git commit -m "Feature"

[main a0ebc67] Feature

1 file changed, 2 insertions(+)

After this procedure, the history looks completely different, although the end result is the same. All commits from the

feature branch have not landed in the main branch, instead, all changes are squashed into a single commit.

$ git log --graph --oneline

* a0ebc67 (HEAD -> main) Feature

* 9ce9b8c Initialize repository

This leads to a linear history and if pull requests are properly reviewed to working commits and therefore to a clean history. Teams working with pull requests usually do such pull request reviews, sometimes even with manual testing, which should avoid having commits that do not work at all.

So by always squashing commits when merging pull requests, it is much easier to keep a clean history with only green

commits. This also ensures that features like git bisect can do their work properly. The only downside with

regards to git bisect I can think of is that it yields bigger commits when pull requests are squashed, which makes

hunting down the error harder since the commit might return hundreds of lines, and not just a few. However, this is

still better than not being able to use the feature at all, because some developers commit code not working properly.

Luckily both

GitHub

and Bitbucket support squashing commits when merging

pull requests.

A completely different approach would be to use continuous

integration, and by that I do not

mean the pipeline running tests, but the process of directly committing to the main branch. This is often combined

with automatic tests, which also helps with keeping a clean history. However, that is a completely different workflow

with other trade-offs. My only recommendation is to try keeping the git history as clean as possible. How that is

done exactly should probably be decided within the team.